| Reye syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Reye's syndrome |

| |

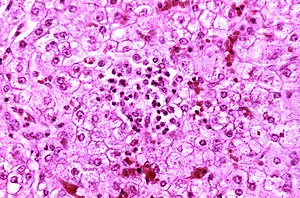

| Appearance of a liver from a child who died of Reye syndrome as seen with a microscope. Hepatocytes are pale-staining due to intracellular fat droplets. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Vomiting, personality changes, confusion, seizures, loss of consciousness |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Risk factors | Aspirin use in children, viral infection |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

| Medication | Mannitol |

| Prognosis | 1⁄3rd long term disability |

| Frequency | Less than one in a million children a year |

| Deaths | ~30% chance of death |

Reye syndrome is a rapidly worsening brain disease. Symptoms may include vomiting, personality changes, confusion, seizures, and loss of consciousness. Even though liver toxicity typically occurs, jaundice usually does not. Death occurs in 20–40% of those affected and about a third of those who survive are left with a significant degree of brain damage.

The cause of Reye syndrome is unknown. It usually begins shortly after recovery from a viral infection, such as influenza or chickenpox. About 90% of cases in children are associated with aspirin (salicylate) use. Inborn errors of metabolism are also a risk factor. Changes on blood tests may include a high blood ammonia level, low blood sugar level, and prolonged prothrombin time. Often the liver is enlarged.

Prevention is typically by avoiding the use of aspirin in children. When aspirin was withdrawn for use in children a decrease of more than 90% in rates of Reye syndrome was seen. Early diagnosis improves outcomes. Treatment is supportive. Mannitol may be used to help with the brain swelling.

The first detailed description of Reye syndrome was in 1963 by Douglas Reye, an Australian pathologist. Children are most commonly affected. It affects fewer than one in a million children a year. The general recommendation to use aspirin in children was withdrawn because of Reye syndrome, with use of aspirin only recommended in Kawasaki disease.

Signs and symptoms

Reye syndrome progresses through five stages:

- Stage I

- Rash on palms of hands and feet

- Persistent, heavy vomiting that is not relieved by not eating

- Generalized lethargy

- Confusion

- Nightmares

- No fever usually present

- Headaches

- Stage II

- Stupor

- Hyperventilation

- Fatty liver (found on biopsy)

- Hyperactive reflexes

- Stage III

- Continuation of Stage I and II symptoms

- Possible coma

- Possible cerebral edema

- Rarely, respiratory arrest

- Stage IV

- Deepening coma

- Dilated pupils with minimal response to light

- Minimal but still present liver dysfunction

- Stage V

- Very rapid onset following stage IV

- Deep coma

- Seizures

- Multiple organ failure

- Flaccidity

- Hyperammonemia (above 300 mg/dL of blood)

- Death

Causes

The cause of Reye syndrome is unknown. It usually begins shortly after recovery from a viral infection, such as influenza or chickenpox. About 90% of cases in children are associated with aspirin (salicylate) use. Inborn errors of metabolism are also a risk factor.

The association with aspirin has been shown through

epidemiological studies. The diagnosis of "Reye Syndrome" greatly

decreased in the 1980s, when genetic testing for inborn errors of metabolism was becoming available in developed countries.

A retrospective study of 49 survivors of cases diagnosed as "Reye's

Syndrome" showed that the majority of the surviving patients had various

metabolic disorders, particularly a fatty-acid oxidation disorder medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency.

Aspirin

There is an association between taking aspirin for viral illnesses and the development of Reye syndrome, but no animal model of Reye syndrome has been developed in which aspirin causes the condition.

The serious symptoms of Reye syndrome appear to result from damage to cellular mitochondria,

at least in the liver, and there are a number of ways that aspirin

could cause or exacerbate mitochondrial damage. A potential increased

risk of developing Reye syndrome is one of the main reasons that aspirin

has not been recommended for use in children and teenagers, the age

group for which the risk of lasting serious effects is highest.

In some countries, oral mouthcare product Bonjela (not the form specifically designed for teething) has labeling cautioning against its use in children, given its salicylate content. There have been no cases of Reye syndrome following its use, and the measure is a precaution. Other medications containing salicylates are often similarly labeled as a precaution.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Surgeon General, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) recommend that aspirin and combination products containing

aspirin not be given to children under 19 years of age during episodes

of fever-causing illnesses. Hence, in the United States,

it is advised that the opinion of a doctor or pharmacist should be

obtained before anyone under 19 years of age is given any medication

containing aspirin (also known on some medicine labels as

acetylsalicylate, salicylate, acetylsalicylic acid, ASA, or salicylic

acid).

Current advice in the United Kingdom by the Committee on Safety of Medicines is that aspirin should not be given to those under the age of 16 years, unless specifically indicated in Kawasaki disease or in the prevention of blood clot formation.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Causes for similar symptoms include

- Various inborn metabolic disorders

- Viral encephalitis

- Drug overdose or poisoning

- Head trauma

- Liver failure due to other causes

- Meningitis

- Kidney failure

- Shaken baby syndrome

Treatment

Prognosis

Documented

cases of Reye syndrome in adults are rare. The recovery of adults with

the syndrome is generally complete, with liver and brain function

returning to normal within two weeks of onset.

In children, mild to severe permanent brain damage is possible,

especially in infants. Over thirty percent of the cases reported in the

United States from 1981 through 1997 resulted in fatality.

Epidemiology

Reye

syndrome occurs almost exclusively in children. While a few adult

cases have been reported over the years, these cases do not typically

show permanent neural or liver damage. Unlike in the United Kingdom, the

surveillance for Reye syndrome in the United States is focused on

people under 18 years of age.

In 1980, after the CDC began cautioning physicians and parents

about the association between Reye syndrome and the use of salicylates

in children with chickenpox or virus-like illnesses, the incidence of

Reye syndrome in the United States began to decline. However, the

decline began prior to the FDA's issue of warning labels on aspirin in 1986.

In the United States between 1980 and 1997, the number of reported

cases of Reye syndrome decreased from 555 cases in 1980 to about two

cases per year since 1994. During this time period 93% of reported cases

for which racial data were available occurred in whites and the median

age was six years. In 93% of cases a viral illness had occurred in the

preceding three-week period. For the period 1991–1994, the annual rate

of hospitalizations due to Reye syndrome in the United States was

estimated to be between 0.2 and 1.1 per million population less than 18

years of age.

During the 1980s, a case-control study carried out in the United

Kingdom also demonstrated an association between Reye syndrome and

aspirin exposure. In June 1986, the United Kingdom Committee on Safety of Medicines

issued warnings against the use of aspirin in children under 12 years

of age and warning labels on aspirin-containing medications were

introduced. United Kingdom surveillance for Reye syndrome documented a

decline in the incidence of the illness after 1986. The reported

incidence rate of Reye syndrome decreased from a high of 0.63 per

100,000 population less than 12 years of age in 1983–1984 to 0.11 in

1990–1991.

From November 1995 to November 1996 in France, a national survey

of pediatric departments for children under 15 years of age with

unexplained encephalopathy

and a threefold (or greater) increase in serum aminotransferase and/or

ammonia led to the identification of nine definite cases of Reye

syndrome (0.79 cases per million children). Eight of the nine children

with Reye syndrome were found to have been exposed to aspirin. In part

because of this survey result, the French Medicines Agency reinforced

the international attention to the relationship between aspirin and Reye

syndrome by issuing its own public and professional warnings about this

relationship.

History

The syndrome is named after Dr. Douglas Reye, who, along with fellow physicians Drs. Graeme Morgan and Jim Baral, published the first study of the syndrome in 1963 in The Lancet.

In retrospect, the occurrence of the syndrome may have first been

reported in 1929. Also in 1964, Dr. George Johnson and colleagues

published an investigation of an outbreak of influenza B that described

16 children who developed neurological problems, four of whom had a

profile remarkably similar to Reye syndrome. Some investigators refer

to this disorder as Reye-Johnson syndrome, although it is more commonly

called Reye syndrome. In 1979, Dr. Karen Starko and colleagues conducted

a case-control study in Phoenix, Arizona, and found the first

statistically-significant link between aspirin use and Reye syndrome. Studies in Ohio and Michigan soon confirmed her findings

pointing to the use of aspirin during an upper respiratory tract or

chickenpox infection as a possible trigger of the syndrome. Beginning

in 1980, the CDC cautioned physicians and parents about the association

between Reye syndrome and the use of salicylates in children and

teenagers with chickenpox or virus-like illnesses. In 1982 the U.S.

Surgeon General issued an advisory, and in 1986 the Food and Drug Administration required a Reye syndrome-related warning label for all aspirin-containing medications.