| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Tryptophan or (2S)-2-amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid

| |

| Other names

2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.723 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C11H12N2O2 | |

| Molar mass | 204.229 g·mol−1 |

| Soluble: 0.23 g/L at 0 °C,

11.4 g/L at 25 °C, 17.1 g/L at 50 °C, 27.95 g/L at 75 °C | |

| Solubility | Soluble in hot alcohol, alkali hydroxides; insoluble in chloroform. |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.38 (carboxyl), 9.39 (amino) |

| -132.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Pharmacology | |

| N06AX02 (WHO) | |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic

data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a non-polar aromatic amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it; it must be obtained from the diet. Tryptophan is also a precursor to the neurotransmitter serotonin, the hormone melatonin and vitamin B3. It is encoded by the codon UGG.

Like other amino acids, tryptophan is a zwitterion at physiological pH where the amino group is protonated (–NH3+; pKa = 9.39) and the carboxylic acid is deprotonated ( –COO−; pKa = 2.38).

Function

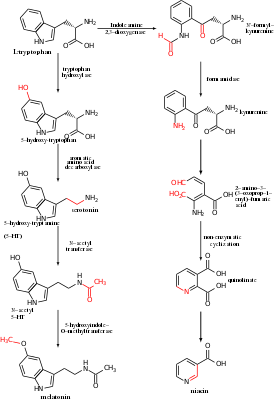

Metabolism of l-tryptophan

into serotonin and melatonin (left) and niacin (right). Transformed

functional groups after each chemical reaction are highlighted in red.

Amino acids, including tryptophan, are used as building blocks in protein biosynthesis, and proteins

are required to sustain life. Many animals (including humans) cannot

synthesize tryptophan: they need to obtain it through their diet, making

it an essential amino acid.

Tryptophan is among the less common amino acids found in proteins, but

it plays important structural or functional roles whenever it occurs.

For instance, tryptophan and tyrosine residues play special roles in "anchoring" membrane proteins within the cell membrane. In addition, tryptophan functions as a biochemical precursor for the following compounds:

- Serotonin (a neurotransmitter), synthesized by tryptophan hydroxylase.

- Melatonin (a neurohormone) is in turn synthesized from serotonin, via N-acetyltransferase and 5-hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase enzymes.

- Niacin, also known as vitamin B3, is synthesized from tryptophan via kynurenine and quinolinic acids.

- Auxins (a class of phytohormones) are synthesized from tryptophan.

The disorder fructose malabsorption causes improper absorption of tryptophan in the intestine, reduced levels of tryptophan in the blood, and depression.

In bacteria that synthesize tryptophan, high cellular levels of this amino acid activate a repressor protein, which binds to the trp operon. Binding of this repressor to the tryptophan operon prevents transcription

of downstream DNA that codes for the enzymes involved in the

biosynthesis of tryptophan. So high levels of tryptophan prevent

tryptophan synthesis through a negative feedback

loop, and when the cell's tryptophan levels go down again,

transcription from the trp operon resumes. This permits tightly

regulated and rapid responses to changes in the cell's internal and

external tryptophan levels.

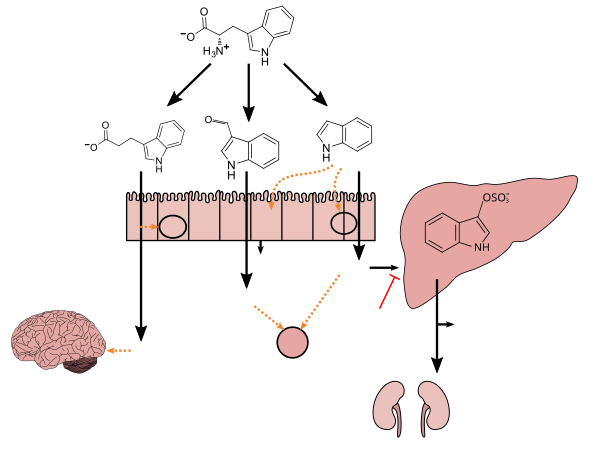

Tryptophan metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota

This diagram shows the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds (indole and certain other derivatives) from tryptophan by bacteria in the gut. Indole is produced from tryptophan by bacteria that express tryptophanase. Clostridium sporogenes metabolizes tryptophan into indole and subsequently 3-indolepropionic acid (IPA), a highly potent neuroprotective antioxidant that scavenges hydroxyl radicals. IPA binds to the pregnane X receptor (PXR) in intestinal cells, thereby facilitating mucosal homeostasis and barrier function. Following absorption from the intestine and distribution to the brain, IPA confers a neuroprotective effect against cerebral ischemia and Alzheimer's disease. Lactobacillus species metabolize tryptophan into indole-3-aldehyde (I3A) which acts on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in intestinal immune cells, in turn increasing interleukin-22 (IL-22) production. Indole itself triggers the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in intestinal L cells and acts as a ligand for AhR. Indole can also be metabolized by the liver into indoxyl sulfate, a compound that is toxic in high concentrations and associated with vascular disease and renal dysfunction. AST-120 (activated charcoal), an intestinal sorbent that is taken by mouth, adsorbs indole, in turn decreasing the concentration of indoxyl sulfate in blood plasma.

|

Recommended dietary allowance

In

2002, the U.S. Institute of Medicine set a Recommended Dietary

Allowance (RDA) of 5 mg/kg body weight/day of Tryptophan for adults 19

years and over.

Dietary sources

Tryptophan is present in most protein-based foods or dietary proteins. It is particularly plentiful in chocolate, oats, dried dates, milk, yogurt, cottage cheese, red meat, eggs, fish, poultry, sesame, chickpeas, almonds, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, buckwheat, spirulina, and peanuts. Contrary to the popular belief that cooked turkey

contains an abundance of tryptophan (with this being used as an

explanation for sleepiness following consumption of the meat), the

tryptophan content in turkey is typical of poultry.

Use as an antidepressant

Because tryptophan is converted into 5-hydroxytryptophan

(5-HTP) which is then converted into the neurotransmitter serotonin, it

has been proposed that consumption of tryptophan or 5-HTP may improve

depression symptoms by increasing the level of serotonin in the brain.

Tryptophan is sold over the counter in the United States (after being banned to varying extents between 1989 and 2005) and the United Kingdom as a dietary supplement for use as an antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sleep aid. It is also marketed as a prescription drug in some European countries for the treatment of major depression. There is evidence that blood tryptophan levels are unlikely to be altered by changing the diet,

but consuming purified tryptophan increases the serotonin level in the

brain, whereas eating foods containing tryptophan does not. This is because the transport system that brings tryptophan across the blood–brain barrier also transports other amino acids which are contained in protein food sources. High blood plasma

levels of other large neutral amino acids prevent the plasma

concentration of tryptophan from increasing brain concentration levels.

In 2001 a Cochrane review

of the effect of 5-HTP and tryptophan on depression was published. The

authors included only studies of a high rigor and included both 5-HTP

and tryptophan in their review because of the limited data on either. Of

108 studies of 5-HTP and tryptophan on depression published between

1966 and 2000, only two met the authors' quality standards for

inclusion, totaling 64 study participants. The substances were more

effective than placebo

in the two studies included but the authors state that "the evidence

was of insufficient quality to be conclusive" and note that "because

alternative antidepressants exist which have been proven to be effective

and safe, the clinical usefulness of 5-HTP and tryptophan is limited at

present". The use of tryptophan as an adjunctive therapy in addition to standard treatment for mood and anxiety disorders is not supported by the scientific evidence.

Side effects

Potential side effects of tryptophan supplementation include nausea, diarrhea, drowsiness, lightheadedness, headache, dry mouth, blurred vision, sedation, euphoria, and nystagmus (involuntary eye movements).

Interactions

Tryptophan taken as a dietary supplement (such as in tablet form) has the potential to cause serotonin syndrome when combined with antidepressants of the MAOI or SSRI class or other strongly serotonergic drugs. Because tryptophan supplementation has not been thoroughly studied in a clinical setting, its interactions with other drugs are not well known.

Isolation

The isolation of tryptophan was first reported by Frederick Hopkins in 1901. Hopkins recovered tryptophan from hydrolysed casein, recovering 4–8 g of tryptophan from 600 g of crude casein.

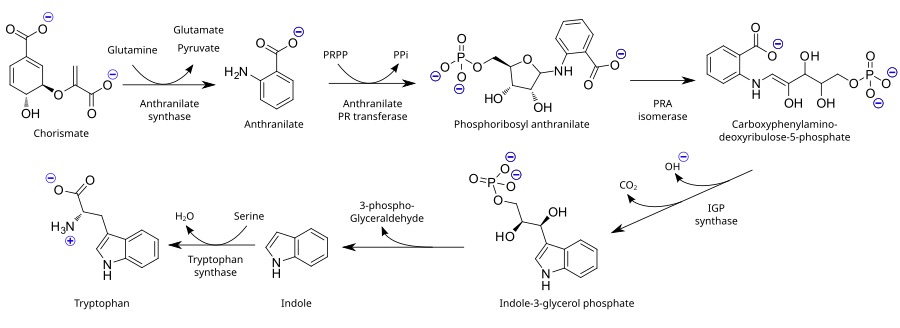

Biosynthesis and industrial production

As

an essential amino acid, tryptophan is not synthesized from simpler

substances in humans and other animals, so it needs to be present in the

diet in the form of tryptophan-containing proteins. Plants and microorganisms commonly synthesize tryptophan from shikimic acid or anthranilate: anthranilate condenses with phosphoribosylpyrophosphate (PRPP), generating pyrophosphate as a by-product. The ring of the ribose moiety is opened and subjected to reductive decarboxylation, producing indole-3-glycerol phosphate; this, in turn, is transformed into indole. In the last step, tryptophan synthase catalyzes the formation of tryptophan from indole and the amino acid serine.

The industrial production of tryptophan is also biosynthetic and is based on the fermentation of serine and indole using either wild-type or genetically modified bacteria such as B. amyloliquefaciens, B. subtilis, C. glutamicum or E. coli. These strains carry mutations that prevent the reuptake of aromatic amino acids or multiple/overexpressed trp operons. The conversion is catalyzed by the enzyme tryptophan synthase.

Society and culture

Eosinophilia–myalgia syndrome

There was a large outbreak of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) in the U.S. in 1989, with more than 1,500 cases reported to the CDC and at least 37 deaths. After preliminary investigation revealed that the outbreak was linked to intake of tryptophan, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recalled tryptophan supplements in 1989 and banned most public sales in 1990, with other countries following suit.

Subsequent studies suggested that EMS was linked to specific

batches of L-tryptophan supplied by a single large Japanese

manufacturer, Showa Denko.

It eventually became clear that recent batches of Showa Denko's

L-tryptophan were contaminated by trace impurities, which were

subsequently thought to be responsible for the 1989 EMS outbreak. However, other evidence suggests that tryptophan itself may be a potentially major contributory factor in EMS.

The FDA loosened its restrictions on sales and marketing of tryptophan in February 2001, but continued to limit the importation of tryptophan not intended for an exempted use until 2005.

The fact that the Showa Denko facility used genetically engineered

bacteria to produce the contaminated batches of L-tryptophan later

found to have caused the outbreak of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome has

been cited as evidence of a need for "close monitoring of the chemical

purity of biotechnology-derived products". Those calling for purity monitoring have, in turn, been criticized as anti-GMO activists who overlook possible non-GMO causes of contamination and threaten the development of biotech.

Turkey meat and drowsiness

A common assertion in the US is that heavy consumption of turkey meat results in drowsiness, due to high levels of tryptophan contained in turkey. However, the amount of tryptophan in turkey is comparable to that contained in other meats. Drowsiness after eating may be caused by other foods eaten with the turkey, particularly carbohydrates. Ingestion of a meal rich in carbohydrates triggers the release of insulin. Insulin in turn stimulates the uptake of large neutral branched-chain amino acids

(BCAA), but not tryptophan, into muscle, increasing the ratio of

tryptophan to BCAA in the blood stream. The resulting increased

tryptophan ratio reduces competition at the large neutral amino acid transporter (which transports both BCAA and aromatic amino acids), resulting in more uptake of tryptophan across the blood–brain barrier into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Once in the CSF, tryptophan is converted into serotonin in the raphe nuclei by the normal enzymatic pathway. The resultant serotonin is further metabolised into melatonin by the pineal gland. Hence, these data suggest that "feast-induced drowsiness"—or postprandial somnolence—may

be the result of a heavy meal rich in carbohydrates, which indirectly

increases the production of melatonin in the brain, and thereby promotes

sleep.

Research

In 1912 Felix Ehrlich demonstrated that yeast attacks the natural amino acids essentially by splitting off carbon dioxide and replacing the amino group with hydroxyl. By this reaction, tryptophan gives rise to tryptophol.

Tryptophan affects brain serotonin synthesis when given orally in

a purified form and is used to modify serotonin levels for research.

Low brain serotonin level is induced by administration of

tryptophan-poor protein in a technique called "acute tryptophan

depletion".

Studies using this method have evaluated the effect of serotonin on

mood and social behavior, finding that serotonin reduces aggression and

increases agreeableness.

Fluorescence

Tryptophan is an important intrinsic fluorescent probe (amino acid),

which can be used to estimate the nature of the microenvironment around

the tryptophan residue. Most of the intrinsic fluorescence emissions of

a folded protein are due to excitation of tryptophan residues.