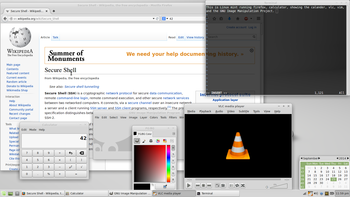

A screenshot of Linux Mint running the Xfce desktop environment, Mozilla Firefox browsing Wikipedia powered by MediaWiki, a calculator program, the built-in calendar, Vim, GIMP, and the VLC media player, all of which are open-source software.

Open-source software (OSS) is a type of computer software in which source code is released under a license in which the copyright holder grants users the rights to use, study, change, and distribute the software to anyone and for any purpose. Open-source software may be developed in a collaborative public manner. Open-source software is a prominent example of open collaboration.

Open-source software development can bring in diverse perspectives beyond those of a single company. A 2008 report by the Standish Group

stated that adoption of open-source software models has resulted in

savings of about $60 billion (£48 billion) per year for consumers.

History

End of 1990s: Foundation of the Open Source Initiative

In

the early days of computing, programmers and developers shared software

in order to learn from each other and evolve the field of computing.

Eventually, the open-source notion moved to the way side of

commercialization of software in the years 1970–1980. However, academics

still often developed software collaboratively. For example, Donald Knuth in 1979 with the TeX typesetting system or Richard Stallman in 1983 with the GNU operating system. In 1997, Eric Raymond published The Cathedral and the Bazaar,

a reflective analysis of the hacker community and free-software

principles. The paper received significant attention in early 1998, and

was one factor in motivating Netscape Communications Corporation to release their popular Netscape Communicator Internet suite as free software. This source code subsequently became the basis behind SeaMonkey, Mozilla Firefox, Thunderbird and KompoZer.

Netscape's act prompted Raymond and others to look into how to bring the Free Software Foundation's

free software ideas and perceived benefits to the commercial software

industry. They concluded that FSF's social activism was not appealing to

companies like Netscape, and looked for a way to rebrand the free software movement to emphasize the business potential of sharing and collaborating on software source code. The new term they chose was "open source", which was soon adopted by Bruce Perens, publisher Tim O'Reilly, Linus Torvalds, and others. The Open Source Initiative was founded in February 1998 to encourage use of the new term and evangelize open-source principles.

While the Open Source Initiative sought to encourage the use of

the new term and evangelize the principles it adhered to, commercial

software vendors found themselves increasingly threatened by the concept

of freely distributed software and universal access to an application's

source code. A Microsoft

executive publicly stated in 2001 that "open source is an intellectual

property destroyer. I can't imagine something that could be worse than

this for the software business and the intellectual-property business." However, while Free and open-source software has historically played a role outside of the mainstream of private software development, companies as large as Microsoft

have begun to develop official open-source presences on the Internet.

IBM, Oracle, Google, and State Farm are just a few of the companies with

a serious public stake in today's competitive open-source market. There

has been a significant shift in the corporate philosophy concerning the

development of FOSS.

The free-software movement

was launched in 1983. In 1998, a group of individuals advocated that

the term free software should be replaced by open-source software (OSS)

as an expression which is less ambiguous and more comfortable for the corporate world. Software developers may want to publish their software with an open-source license,

so that anybody may also develop the same software or understand its

internal functioning. With open-source software, generally, anyone is

allowed to create modifications of it, port it to new operating systems

and instruction set architectures,

share it with others or, in some cases, market it. Scholars Casson and

Ryan have pointed out several policy-based reasons for adoption of open

source – in particular, the heightened value proposition from open

source (when compared to most proprietary formats) in the following

categories:

- Security

- Affordability

- Transparency

- Perpetuity

- Interoperability

- Flexibility

- Localization – particularly in the context of local governments (who make software decisions). Casson and Ryan argue that "governments have an inherent responsibility and fiduciary duty to taxpayers" which includes the careful analysis of these factors when deciding to purchase proprietary software or implement an open-source option.

The Open Source Definition

presents an open-source philosophy and further defines the terms of

use, modification and redistribution of open-source software. Software

licenses grant rights to users which would otherwise be reserved by

copyright law to the copyright holder. Several open-source software

licenses have qualified within the boundaries of the Open Source Definition. The most prominent and popular example is the GNU General Public License

(GPL), which "allows free distribution under the condition that further

developments and applications are put under the same licence", thus

also free.

The open source label came out of a strategy session held on April 7, 1998 in Palo Alto in reaction to Netscape's January 1998 announcement of a source code release for Navigator (as Mozilla). A group of individuals at the session included Tim O'Reilly, Linus Torvalds, Tom Paquin, Jamie Zawinski, Larry Wall, Brian Behlendorf, Sameer Parekh, Eric Allman, Greg Olson, Paul Vixie, John Ousterhout, Guido van Rossum, Philip Zimmermann, John Gilmore and Eric S. Raymond.[17] They used the opportunity before the release of Navigator's source code to clarify a potential confusion caused by the ambiguity of the word "free" in English.

Many people claimed that the birth of the Internet, since 1969, started the open-source movement, while others do not distinguish between open-source and free software movements.

The Free Software Foundation (FSF), started in 1985, intended the word "free" to mean freedom to distribute (or "free as in free speech") and not freedom from cost

(or "free as in free beer"). Since a great deal of free software

already was (and still is) free of charge, such free software became

associated with zero cost, which seemed anti-commercial.

The Open Source Initiative

(OSI) was formed in February 1998 by Eric Raymond and Bruce Perens.

With at least 20 years of evidence from case histories of closed

software development versus open development already provided by the

Internet developer community, the OSI presented the "open source" case

to commercial businesses, like Netscape. The OSI hoped that the use of

the label "open source", a term suggested by Christine Peterson of the Foresight Institute

at the strategy session, would eliminate ambiguity, particularly for

individuals who perceive "free software" as anti-commercial. They sought

to bring a higher profile to the practical benefits of freely available

source code, and they wanted to bring major software businesses and

other high-tech industries into open source. Perens attempted to

register "open source" as a service mark for the OSI, but that attempt was impractical by trademark

standards. Meanwhile, due to the presentation of Raymond's paper to the

upper management at Netscape—Raymond only discovered when he read the press release, and was called by Netscape CEO Jim Barksdale's PA later in the day—Netscape released its Navigator source code as open source, with favorable results.

Definitions

The logo of the Open Source Initiative

The Open Source Initiative's (OSI) definition is recognized by several governments internationally as the standard or de facto

definition. In addition, many of the world's largest

open-source-software projects and contributors, including Debian, Drupal

Association, FreeBSD Foundation, Linux Foundation, OpenSUSE Foundation,

Mozilla Foundation, Wikimedia Foundation, Wordpress Foundation have

committed to upholding the OSI's mission and Open Source Definition through the OSI Affiliate Agreement.

OSI uses The Open Source Definition to determine whether it considers a software license open source. The definition was based on the Debian Free Software Guidelines, written and adapted primarily by Perens. Perens did not base his writing on the "four freedoms" from the Free Software Foundation (FSF), which were only widely available later.

Under Perens' definition, open source is a broad software

license that makes source code available to the general public with

relaxed or non-existent restrictions on the use and modification of the

code. It is an explicit "feature" of open source that it puts very few

restrictions on the use or distribution by any organization or user, in

order to enable the rapid evolution of the software.

Despite initially accepting it, Richard Stallman

of the FSF now flatly opposes the term "Open Source" being applied to

what they refer to as "free software". Although he agrees that the two

terms describe "almost the same category of software", Stallman

considers equating the terms incorrect and misleading. Stallman also opposes the professed pragmatism of the Open Source Initiative,

as he fears that the free software ideals of freedom and community are

threatened by compromising on the FSF's idealistic standards for

software freedom. The FSF considers free software to be a subset of open-source software, and Richard Stallman explained that DRM

software, for example, can be developed as open source, despite that it

does not give its users freedom (it restricts them), and thus doesn't

qualify as free software.

Open-source software licensing

When an author contributes code to an open-source project (e.g.,

Apache.org) they do so under an explicit license (e.g., the Apache

Contributor License Agreement) or an implicit license (e.g. the

open-source license under which the project is already licensing code).

Some open-source projects do not take contributed code under a license,

but actually require joint assignment of the author's copyright in order

to accept code contributions into the project.

Examples of free software license / open-source licenses include Apache License, BSD license, GNU General Public License, GNU Lesser General Public License, MIT License, Eclipse Public License and Mozilla Public License.

The proliferation of open-source licenses

is a negative aspect of the open-source movement because it is often

difficult to understand the legal implications of the differences

between licenses. With more than 180,000 open-source projects available

and more than 1400 unique licenses, the complexity of deciding how to

manage open-source use within "closed-source" commercial enterprises has

dramatically increased. Some are home-grown, while others are modeled

after mainstream FOSS

licenses such as Berkeley Software Distribution ("BSD"), Apache,

MIT-style (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), or GNU General Public

License ("GPL"). In view of this, open-source practitioners are

starting to use classification schemes in which FOSS licenses are grouped (typically based on the existence and obligations imposed by the copyleft provision; the strength of the copyleft provision).

An important legal milestone for the open source / free software

movement was passed in 2008, when the US federal appeals court ruled

that free software licenses

definitely do set legally binding conditions on the use of copyrighted

work, and they are therefore enforceable under existing copyright law.

As a result, if end-users violate the licensing conditions, their

license disappears, meaning they are infringing copyright.

Despite this licensing risk, most commercial software vendors are using

open-source software in commercial products while fulfilling the license

terms, e.g. leveraging the Apache license.

Certifications

Certification

can help to build user confidence. Certification could be applied to

the simplest component, to a whole software system. The United Nations University International Institute for Software Technology,

initiated a project known as "The Global Desktop Project". This project

aims to build a desktop interface that every end-user is able to

understand and interact with, thus crossing the language and cultural

barriers. The project would improve developing nations' access to

information systems. UNU/IIST hopes to achieve this without any

compromise in the quality of the software by introducing certifications.

Open-source software development

Development model

In his 1997 essay The Cathedral and the Bazaar, open-source evangelist Eric S. Raymond suggests a model for developing OSS known as the bazaar

model. Raymond likens the development of software by traditional

methodologies to building a cathedral, "carefully crafted by individual

wizards or small bands of mages working in splendid isolation".

He suggests that all software should be developed using the bazaar

style, which he described as "a great babbling bazaar of differing

agendas and approaches."

In the traditional model of development, which he called the cathedral

model, development takes place in a centralized way. Roles are clearly

defined. Roles include people dedicated to designing (the architects),

people responsible for managing the project, and people responsible for

implementation. Traditional software engineering follows the cathedral

model.

The bazaar model, however, is different. In this model, roles are not clearly defined. Gregorio Robles suggests that software developed using the bazaar model should exhibit the following patterns:

- Users should be treated as co-developers

- The users are treated like co-developers and so they should have access to the source code of the software. Furthermore, users are encouraged to submit additions to the software, code fixes for the software, bug reports, documentation, etc. Having more co-developers increases the rate at which the software evolves. Linus's law states, "Given enough eyeballs all bugs are shallow." This means that if many users view the source code, they will eventually find all bugs and suggest how to fix them. Note that some users have advanced programming skills, and furthermore, each user's machine provides an additional testing environment. This new testing environment offers the ability to find and fix a new bug.

- Early releases

- The first version of the software should be released as early as possible so as to increase one's chances of finding co-developers early.

- Frequent integration

- Code changes should be integrated (merged into a shared code base) as often as possible so as to avoid the overhead of fixing a large number of bugs at the end of the project life cycle. Some open-source projects have nightly builds where integration is done automatically on a daily basis.

- Several versions

- There should be at least two versions of the software. There should be a buggier version with more features and a more stable version with fewer features. The buggy version (also called the development version) is for users who want the immediate use of the latest features, and are willing to accept the risk of using code that is not yet thoroughly tested. The users can then act as co-developers, reporting bugs and providing bug fixes.

- High modularization

- The general structure of the software should be modular allowing for parallel development on independent components.

- Dynamic decision-making structure

- There is a need for a decision-making structure, whether formal or informal, that makes strategic decisions depending on changing user requirements and other factors. Compare with extreme programming.

Data suggests, however, that OSS is not quite as democratic as the

bazaar model suggests. An analysis of five billion bytes of

free/open-source code by 31,999 developers shows that 74% of the code

was written by the most active 10% of authors. The average number of

authors involved in a project was 5.1, with the median at 2.

Advantages and disadvantages

Open-source

software is usually easier to obtain than proprietary software, often

resulting in increased use. Additionally, the availability of an

open-source implementation of a standard can increase adoption of that

standard. It has also helped to build developer loyalty as developers feel empowered and have a sense of ownership of the end product.

Moreover, lower costs of marketing and logistical services are

needed for OSS. It is a good tool to promote a company's image,

including its commercial products. The OSS development approach has helped produce reliable, high quality software quickly and inexpensively.

Open-source development offers the potential for a more flexible

technology and quicker innovation. It is said to be more reliable since

it typically has thousands of independent programmers testing and fixing

bugs of the software. Open source is not dependent on the company or

author that originally created it. Even if the company fails, the code

continues to exist and be developed by its users. Also, it uses open

standards accessible to everyone; thus, it does not have the problem of

incompatible formats that may exist in proprietary software.

It is flexible because modular systems allow programmers to build

custom interfaces, or add new abilities to it and it is innovative

since open-source programs are the product of collaboration among a

large number of different programmers. The mix of divergent

perspectives, corporate objectives, and personal goals speeds up

innovation.

Moreover, free software can be developed in accord with purely

technical requirements. It does not require thinking about commercial

pressure that often degrades the quality of the software. Commercial

pressures make traditional software developers pay more attention to

customers' requirements than to security requirements, since such

features are somewhat invisible to the customer.

It is sometimes said that the open-source development process may

not be well defined and the stages in the development process, such as

system testing and documentation may be ignored. However this is only

true for small (mostly single programmer) projects. Larger, successful

projects do define and enforce at least some rules as they need them to

make the teamwork possible. In the most complex projects these rules may be as strict as reviewing even minor change by two independent developers.

Not all OSS initiatives have been successful, for example SourceXchange and Eazel.

Software experts and researchers who are not convinced by open source's

ability to produce quality systems identify the unclear process, the

late defect discovery and the lack of any empirical evidence as the most

important problems (collected data concerning productivity and

quality).

It is also difficult to design a commercially sound business model

around the open-source paradigm. Consequently, only technical

requirements may be satisfied and not the ones of the market.

In terms of security, open source may allow hackers to know about the

weaknesses or loopholes of the software more easily than closed-source

software. It depends on control mechanisms in order to create effective

performance of autonomous agents who participate in virtual

organizations.

Development tools

In OSS development, tools are used to support the development of the product and the development process itself.

Revision control systems such as Concurrent Versions System (CVS) and later Subversion (SVN) and Git

are examples of tools, often themselves open source, help manage the

source code files and the changes to those files for a software project. The projects are frequently hosted and published on source-code-hosting facilities such as Launchpad.

Open-source projects are often loosely organized with "little

formalised process modelling or support", but utilities such as issue

trackers are often used to organize open-source software development. Commonly used bugtrackers include Bugzilla and Redmine.

Tools such as mailing lists and IRC provide means of coordination among developers. Centralized code hosting sites also have social features that allow developers to communicate.

Organizations

Some of the "more prominent organizations" involved in OSS development include the Apache Software Foundation, creators of the Apache web server; the Linux Foundation, a nonprofit which as of 2012 employed Linus Torvalds, the creator of the Linux operating system kernel; the Eclipse Foundation, home of the Eclipse software development platform; the Debian Project, creators of the influential Debian GNU/Linux distribution; the Mozilla Foundation, home of the Firefox web browser; and OW2,

European-born community developing open-source middleware. New

organizations tend to have a more sophisticated governance model and

their membership is often formed by legal entity members.

Open Source Software Institute

is a membership-based, non-profit (501 (c)(6)) organization established

in 2001 that promotes the development and implementation of open source

software solutions within US Federal, state and local government

agencies. OSSI's efforts have focused on promoting adoption of

open-source software programs and policies within Federal Government and

Defense and Homeland Security communities.

Open Source for America

is a group created to raise awareness in the United States Federal

Government about the benefits of open-source software. Their stated

goals are to encourage the government's use of open source software,

participation in open-source software projects, and incorporation of

open-source community dynamics to increase government transparency.

Mil-OSS is a group dedicated to the advancement of OSS use and creation in the military.

Funding

Companies whose business center on the development of open-source software

employ a variety of business models to solve the challenge of how to

make money providing software that is by definition licensed free of

charge. Each of these business strategies rests on the premise that

users of open-source technologies are willing to purchase additional

software features under proprietary licenses, or purchase other services

or elements of value that complement the open-source software that is

core to the business. This additional value can be, but not limited to,

enterprise-grade features and up-time guarantees (often via a service-level agreement)

to satisfy business or compliance requirements, performance and

efficiency gains by features not yet available in the open source

version, legal protection (e.g., indemnification from copyright or

patent infringement), or professional support/training/consulting that

are typical of proprietary software applications.

Comparisons with other software licensing/development models

Closed source / proprietary software

The debate over open source vs. closed source (alternatively called proprietary software) is sometimes heated.

The top four reasons (as provided by Open Source Business Conference survey) individuals or organizations choose open-source software are:

- lower cost

- security

- no vendor 'lock in'

- better quality

Since innovative companies no longer rely heavily on software sales, proprietary software has become less of a necessity. As such, things like open-source content management system—or CMS—deployments are becoming more commonplace. In 2009, the US White House switched its CMS system from a proprietary system to Drupal open source CMS. Further, companies like Novell

(who traditionally sold software the old-fashioned way) continually

debate the benefits of switching to open-source availability, having

already switched part of the product offering to open source code. In this way, open-source software provides solutions to unique or specific problems. As such, it is reported that 98% of enterprise-level companies use open-source software offerings in some capacity.

With this market shift, more critical systems are beginning to rely on open-source offerings, allowing greater funding (such as US Department of Homeland Security grants)

to help "hunt for security bugs." According to a pilot study of

organizations adopting (or not adopting) OSS, the following factors of

statistical significance were observed in the manager's beliefs: (a)

attitudes toward outcomes, (b) the influences and behaviors of others,

and (c) their ability to act.

Proprietary source distributors have started to develop and

contribute to the open-source community due to the market share shift,

doing so by the need to reinvent their models in order to remain

competitive.

Many advocates argue that open-source software is inherently safer because any person can view, edit, and change code.

A study of the Linux source code has 0.17 bugs per 1000 lines of code

while proprietary software generally scores 20–30 bugs per 1000 lines.

Free software

According to the Free software movement's leader, Richard Stallman, the main difference is that by choosing one term over the other (i.e. either "open source" or "free software")

one lets others know about what one's goals are: "Open source is a

development methodology; free software is a social movement." Nevertheless, there is significant overlap between open source software and free software.

The FSF

said that the term "open source" fosters an ambiguity of a different

kind such that it confuses the mere availability of the source with the

freedom to use, modify, and redistribute it. On the other hand, the

"free software" term was criticized for the ambiguity of the word "free"

as "available at no cost", which was seen as discouraging for business

adoption, and for the historical ambiguous usage of the term.

Developers have used the alternative terms Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), or Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS), consequently, to describe open-source software that is also free software. While the definition of open source software is very similar to the FSF's free software definition it was based on the Debian Free Software Guidelines, written and adapted primarily by Bruce Perens with input from Eric S. Raymond and others.

The term "open source" was originally intended to be

trademarkable; however, the term was deemed too descriptive, so no

trademark exists.

The OSI would prefer that people treat open source as if it were a

trademark, and use it only to describe software licensed under an OSI

approved license.

OSI Certified is a trademark licensed only to people who

are distributing software licensed under a license listed on the Open

Source Initiative's list.

Open-source versus source-available

Although the OSI definition of "open-source software" is widely

accepted, a small number of people and organizations use the term to

refer to software where the source is available for viewing, but which

may not legally be modified or redistributed. Such software is more

often referred to as source-available, or as shared source, a term coined by Microsoft in 2001. While in 2007 two of Microsoft's Shared Source Initiative licenses were certified by the OSI, most licenses from the SSI program are still source-available only.

Open-sourcing

Open-sourcing is the act of propagating the open source movement, most often referring to releasing previously proprietary software under an open source/free software license, but it may also refer programming Open Source software or installing Open Source software.

Notable software packages, previously proprietary, which have been open sourced include:

- Netscape Navigator, the code of which became the basis of the Mozilla and Mozilla Firefox web browsers

- StarOffice, which became the base of the OpenOffice.org office suite and LibreOffice

- Global File System, was originally GPL'd, then made proprietary in 2001(?), but in 2004 was re-GPL'd.

- SAP DB, which has become MaxDB, and is now distributed (and owned) by MySQL AB

- InterBase database, which was open sourced by Borland in 2000 and presently exists as a commercial product and an open-source fork (Firebird)

Before changing the license of software, distributors usually audit

the source code for third party licensed code which they would have to

remove or obtain permission for its relicense. Backdoors and other malware should also be removed as they may easily be discovered after release of the code.

Current applications and adoption

"We migrated key

functions from Windows to Linux because we needed an operating system

that was stable and reliable – one that would give us in-house control.

So if we needed to patch, adjust, or adapt, we could."

Official statement of the United Space Alliance, which manages the computer systems for the International Space Station (ISS), regarding why they chose to switch from Windows to Debian GNU/Linux on the ISS

Widely used open-source software

Open-source software projects are built and maintained by a network

of volunteer programmers and are widely used in free as well as

commercial products. Prime examples of open-source products are the Apache HTTP Server, the e-commerce platform osCommerce, internet browsers Mozilla Firefox and Chromium (the project where the vast majority of development of the freeware Google Chrome is done) and the full office suite LibreOffice. One of the most successful open-source products is the GNU/Linux operating system, an open-source Unix-like operating system, and its derivative Android, an operating system for mobile devices. In some industries, open-source software is the norm.

Extensions for non-software use

While the term "open source" applied originally only to the source code of software, it is now being applied to many other areas such as Open source ecology,

a movement to decentralize technologies so that any human can use them.

However, it is often misapplied to other areas that have different and

competing principles, which overlap only partially.

The same principles that underlie open-source software can be found in many other ventures, such as open-source hardware, Wikipedia, and open-access publishing. Collectively, these principles are known as open source, open content, and open collaboration:

"any system of innovation or production that relies on goal-oriented

yet loosely coordinated participants, who interact to create a product

(or service) of economic value, which they make available to

contributors and non-contributors alike."

This "culture" or ideology takes the view that the principles

apply more generally to facilitate concurrent input of different

agendas, approaches, and priorities, in contrast with more centralized

models of development such as those typically used in commercial

companies.